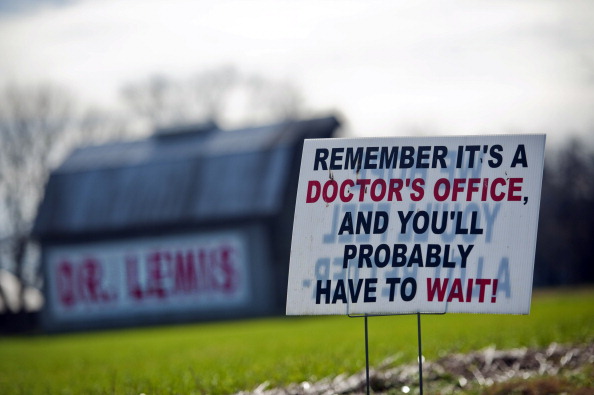

Early memories of my local physician in Rolesville, NC are not associated with feelings of love and loyalty. Our community was served by two hometown physicians: one with an office in his home, a Marcus Welby, MD, clone in Wake Forest, NC, and one with a free-standing office that was open 7 days a week in Rolesville, NC.

Appointments were never scheduled and the wait to see a physician was hours. In 1979 my grandfather died in the office of our rural physician. He was never taken to community hospital ER across the street and there was no “crash cart” in the doctor’s office. His death certificate reads “cardiac arrest.” This rural physician retired some years later.

In the fall of 1974 I needed copies of my immunization records for a college application. He told me to meet him at his “farm” and I followed him to an abandoned barn on the property where all of the patient paper medical records were piled in boxes. He located my “file’ and transcribed by hand the dates of my immunizations on to the college form. Final disposition of an entire physician’s practice of patient records is unknown as the farm has long since been demolished.

Living in the rural South is often depicted by Magnolias, azaleas, Charleston plantations, and sweet tea. Front porches filled with rocking chairs and overflowing garden containers of flowers in full bloom color the Southern landscape. Each person in a rural community requires healthcare and a physician to oversee their care from birth through their geriatric years.

People who live in rural communities seek medical care in their geographic area and are less likely to drive to a major city to see a physician. A “hometown” physician can be revered as “God-Like” for their knowledge and expertise in clinical medicine. Community populations are “loyal” to the physician and are hesitant to seek a second opinion or evaluation by a specialist. Additional factors that inhibit patients from seeking medical evaluation outside their local area may be transportation limitations, poor internet access for research, and basic education.

Small town physicians are revered as the “expert” in all medical conditions. They may also be the “primary care” physician and have contracts with local companies who refer employees for work-injury evaluations. Local companies can include home health agencies, schools, construction companies, freight carriers, and private businesses.

This “one man rural physician” office is probably not equipped with a full laboratory and/or imaging equipment for “STAT” evaluations. In office medical examinations are limited to physical exams, dipstick UA, vital signs, otoscope, weight, and height. Full laboratory panels require pick up and analysis by a major laboratory such as Quest Diagnostics or LabCorp. Offices should able to refer to an imaging center; however, this requires the patient to travel to the center for evaluation. Equipment and laboratory limitations with the onsite physician’s office leaves a “work injury patient” without a comprehensive medical examination.

The rural physician’s diagnosis is considered “solid” by the referring business and the work injury patient left with a questionable diagnosis that directly impacts their ability to apply for Worker’s Compensation or Disability Insurance Claims. A physician’s relationship with the referring business entity could be a potential conflict of interest and not allow the injury patient to receive an unbiased assessment.

What needs to be monitored to ensure rural physicians are in compliance with state and federal regulations? First, a current medical license is a state requirement throughout the US. However, continuing education requirements for rural physicians are not monitored unless there is a state requirement. This leaves rural communities susceptible to a physician working in their community for 40 years who may not attend a continuing education course since completing their Residency or Fellowship.

Second, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, requires all public and private healthcare providers and other eligible professionals to adopt and demonstrate “meaningful use” of electronic medical records (EMR) by January 1, 2014 in order to maintain their existing Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement levels. All EMRs are not HIPAA compliant and a patient’s data can be compromised with EMR systems that are not 21CFR Part 11 Compliant.

How do we bring changes and more healthcare options to small towns? An increase in community outreach programs from state medical schools is urgently needed. Medical school attending physicians, medical students, interns, residents and fellows bring extensive knowledge and expertise to communities. This allows access to state-of-the-art diagnostic methods and medical experts.

Patient Advocacy is an excellent method to increase education, training and awareness in communities. Local television stations should increase media coverage of healthcare topics in the rural communities which they serve.

Community awareness and local education is required through programs in churches, schools, local technical colleges and support groups to educate community residents in healthcare best practices and ongoing healthcare issues. Local government leaders should make healthcare improvements part of their annual budget and platform.

Each community needs more than one physician to allow rural Americans a choice in physician care, management, and option for a local second opinion. Rural communities should be enabled to make a choice in their physician and provided with options within their geographic region to seek a second expert opinion for an accurate diagnosis.

PHOTO CREDIT: Getty Images/The Washington Post

Recent Comments